In this conversation, we map out the myriad of ways time is involved in an artist’s work. With the hyper detailing of Kenn’s work and his prolific output, it seems a wonder he has enough time to do it all. Let’s find out the ingredients to his mastery of time.

CONVERSATION.06

EXPLORING TIME, IN ALL ITS MANY FORMS

If you were to speak about the concept of “time” as a professional artist, where would you begin?

K: When I first began the serious intention of a studio and a practice as a business, time took on new meaning. Coming from an arts education background where concept, process, and theory were the main ingredients, I never considered time. I just put the time into it. But, when art became my business, I needed to rectify time, and see time as valuable and productive. So I began to think about it – not just qualitatively, but also quantitatively.

Michelle was so important in this because at one point she asked me, “How much time is involved in this 3 foot by 4 foot painting. You sold a number of those.” And, I found, I didn’t have an answer. So she suggested I log my time.

So that’s exactly what I began to do. This set me up to see the time involved in the fabrication of my drawings and paintings. We could then take that data, and calculate an hourly rate, like we did for our graphic design business at the time. Once I had a price for my time, I would double that amount since a gallerist would take 50% of the sale, and also add the amount I spent on materials. This is how we began to equate a monetary value for the work as a product. This created a consistent pricing structure.

Keep in mind, paintings are not the same as products like gasoline or milk. These types of products can change or alter depending on where you buy them. For example, they will be more expensive in California where the cost of living and taxation are higher. But a painting by DeKooning that is a million dollars in New York is still going to be a million dollars in Tokyo. It has a universal pricing structure.

I really began to respect the idea of time because of Michelle. She excels within management and logistics and truly helped me establish a structure for tracking jobs and projects. We would also categorize them: whether they were commissions, exhibitions, proposals, etc., so we were managing the work just like in our graphic design business. We still utilize this job tracking system to assist us in knowing in what phase each job is. This is essential, as I am always working on many proposals, paintings, series, and experimentations at the same time.

Then, we have another book entirely that logs communications: emails, phone calls, etc., that helps keep us all on the same page and tracks the progress of a project. This has taken away all of the back-end anxiety of the status of everything. Michelle manages the business and organizational aspect of the studio so well. This makes my studio time much more valuable and productive, and gives me much more freedom in the creative process. That’s what every artist needs. It is much more difficult to flip back and forth from creating to accounting, or from exploring to drawing up a proposal.

She and I still work in tandem. We’re sending out quite a few proposals right now. I will start the writing process, and then I will send it to her. Then, she will inquire what I mean and combine it with other language that a non-artisan can understand. I am so appreciative of her for that because I wouldn’t be here without that.

There are other people involved as well. Margaret Marchuk helps us with PR and marketing. She and Michelle will collaborate to create opportunities to spread the word about my work, like this podcast interview with NPR.

I realize that time is so valuable in the process, and that we need a team to pull this off. No one lives in a vacuum. I’m not reinventing the wheel – I’m just adding another spoke to that wheel. Having these other people work with me is priceless. It gifts me time in the studio to experiment, to interrogate, and to explore.

Knowing your work, there does not seem to be a linear path for time. It sounds like you measure the productive time for a piece, but how to you quantify time when you are upcycling a former piece you have done?

Also the collective time of your art career, experience, and data you have absorbed over your lifetime. How do you qualify this time? Your train of thought, the fact that you can output at a certain pace. I am guessing you are much quicker at articulating the initial idea or exploration now that you have many years in this field.

K: I’m not sure I am. I like the word collective. When you think about thought process, I just keeping adding on. I build upon the strata. But this also gives me a lot more information to mine. So, it does not necessarily make the conceptual process quicker. Some things are quicker time wise. But then there’s also the time when I’m not even producing, I’m just looking.

I thought of this the other day: what if there were a device that you could hook up to your brain that would parse and collect data? We are constantly responding to our surroundings. If I say a painting took me 40 hours to complete, that’s still not the whole picture.

It seems impossible to calculate all of the factors involved when creating a piece. It’s timeless when you start to add up all the time noticing, pondering, and collecting data. And, is the same for you, like other creative people where an idea or inspiration might strike at odd times, like when you first lay your head down to go to sleep?

K: Yes. Creativity does not respect the habitual nature of our lives. For me, it often interrupts something, like sitting down for dinner. I’ll have to stop what I am doing and run to the studio.

So, what people are getting, when they purchase one of your pieces, it’s not just 40 hours of producing. They get a piece of your life. That sounds weird, but do you know what I am trying to say?

K: Sure. You could categorize that portion of the work as the psychological, philosophical part of the piece.

That’s what makes it, not just a mere image (like just seeing a digital image of it on social media), but a valuable piece that you can stand in front of and behold.

K: When someone asks me how long it took me to do a piece, sometimes I answer, “It took me 62 years.” Because it is that accumulation of collective thought, experiences, and practice that brought me to that point.

In the creative process, there is output, and input. I know you have quite an art book collection. How do you figure the time it takes to feed your creativity and process? It sounds like this is an all-consuming way of life for you – there’s a constant flow of information.

K: Well in addition to being an artist, being a reader and researcher are major components to my existence. But those are just labels, right? Oftentimes we have to speak in terms of labeling for others to understand. Because in many ways, this entire process is difficult to language. Here, we are just doing our best to define, articulate, and pinpoint some key words to this expansive, abstract concept of time. So much of my creative process is not holding a paint brush or tool in my hand. Much of my time is spent doing other things, like riding a bicycle. That’s when a painting will come up in my mind, and I will realize that an element of that piece should move, or change color.

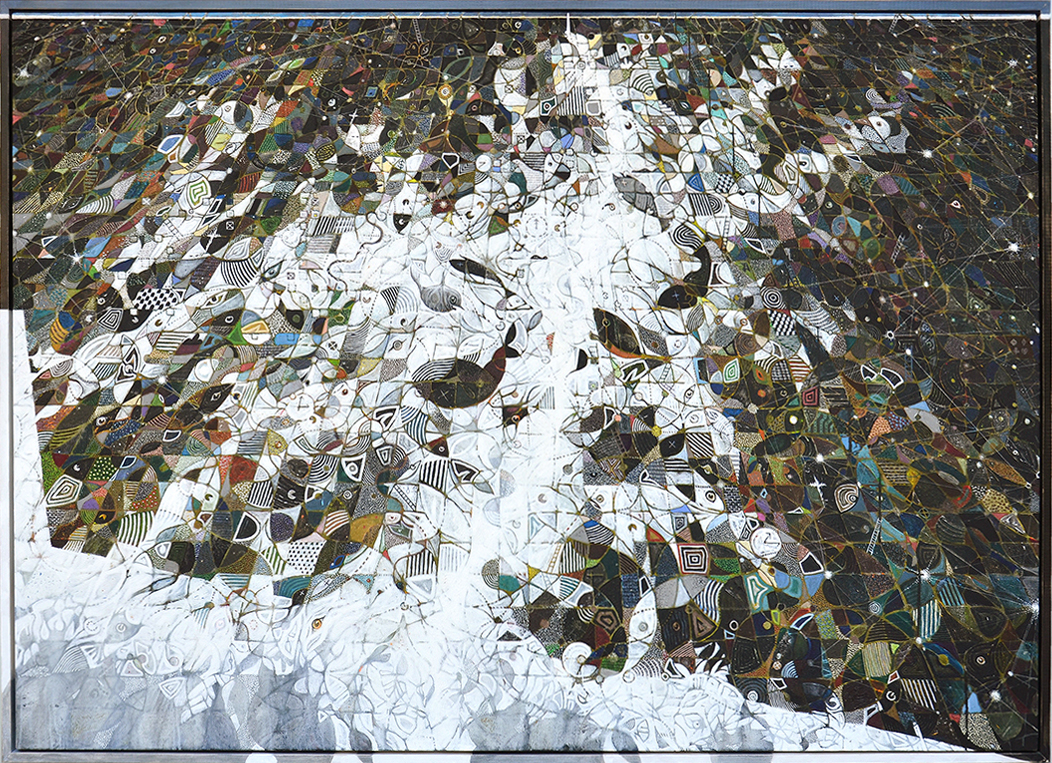

overtopping

2019, mixed media on canvas & wood, 62×86 inches

overtopping

(in progress)

In the case of the painting, “overtopping,” which was all yellow, I realized I needed to cover it with black because that yellow wasn’t working. Then it needed something more, so I decided to sand it. Even this was not a linear process. After I covered it with black, I had to let that phase ruminate for a while.

In the case of the painting, “overtopping,” which was all yellow, I realized I needed to cover it with black because that yellow wasn’t working. Then it needed something more, so I decided to sand it. Even this was not a linear process. After I covered it with black, I had to let that phase ruminate for a while.

overtopping

(details 1 and 2)

If you read, and a new concept comes into your being, you don’t know how to understand that, or what to do with it. You need time for that idea to churn, like on your bike, to process that information.

K: This makes me think of the book I’m currently reading called, “The Geometry of Grief.” This mathematician writes about the grief we experience, for example, when we lose a loved one. But he also talks about the more subtle forms of grief. Like when an incredible idea first surfaces it’s exciting. A feeling of grief arises afterwards, though, when you realize that you will never have that level of exaltation again.

So, after that first exciting moment with an idea, the flame kind of flickers out. It takes discipline to follow up on that idea, see it through, and produce it.

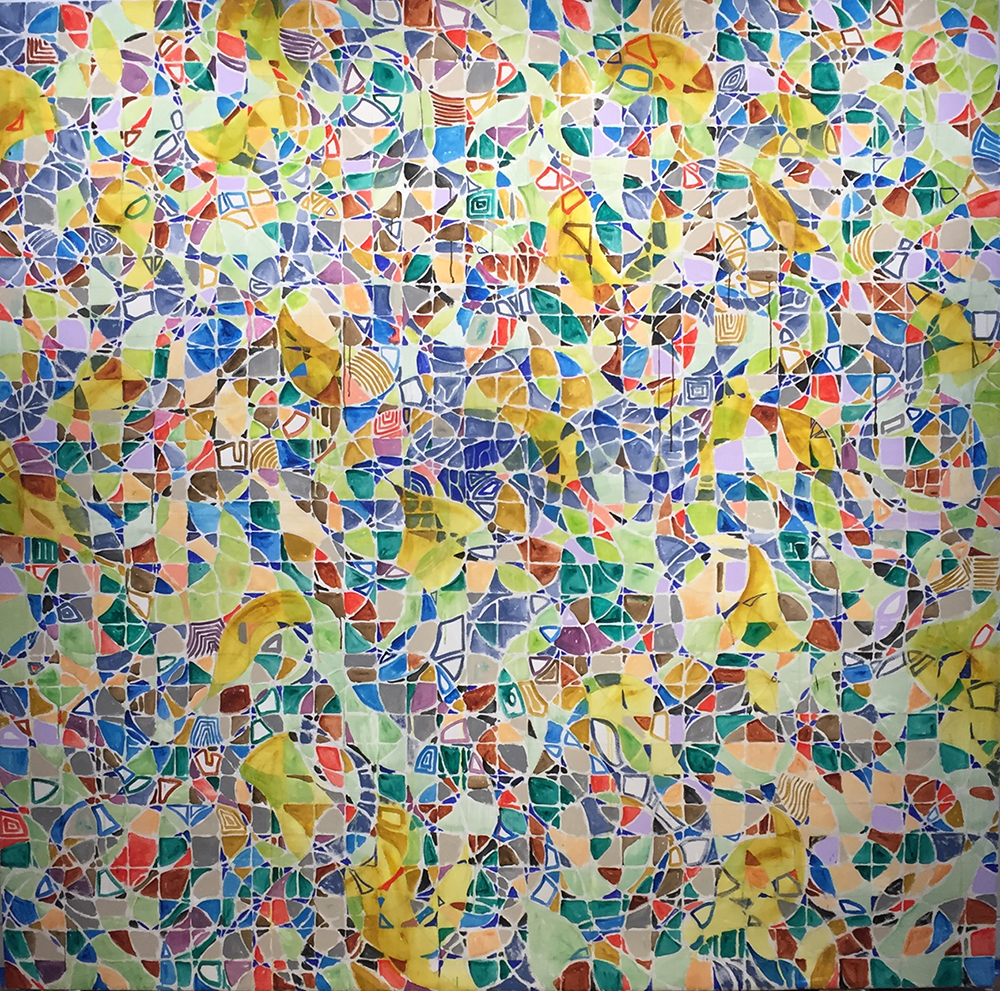

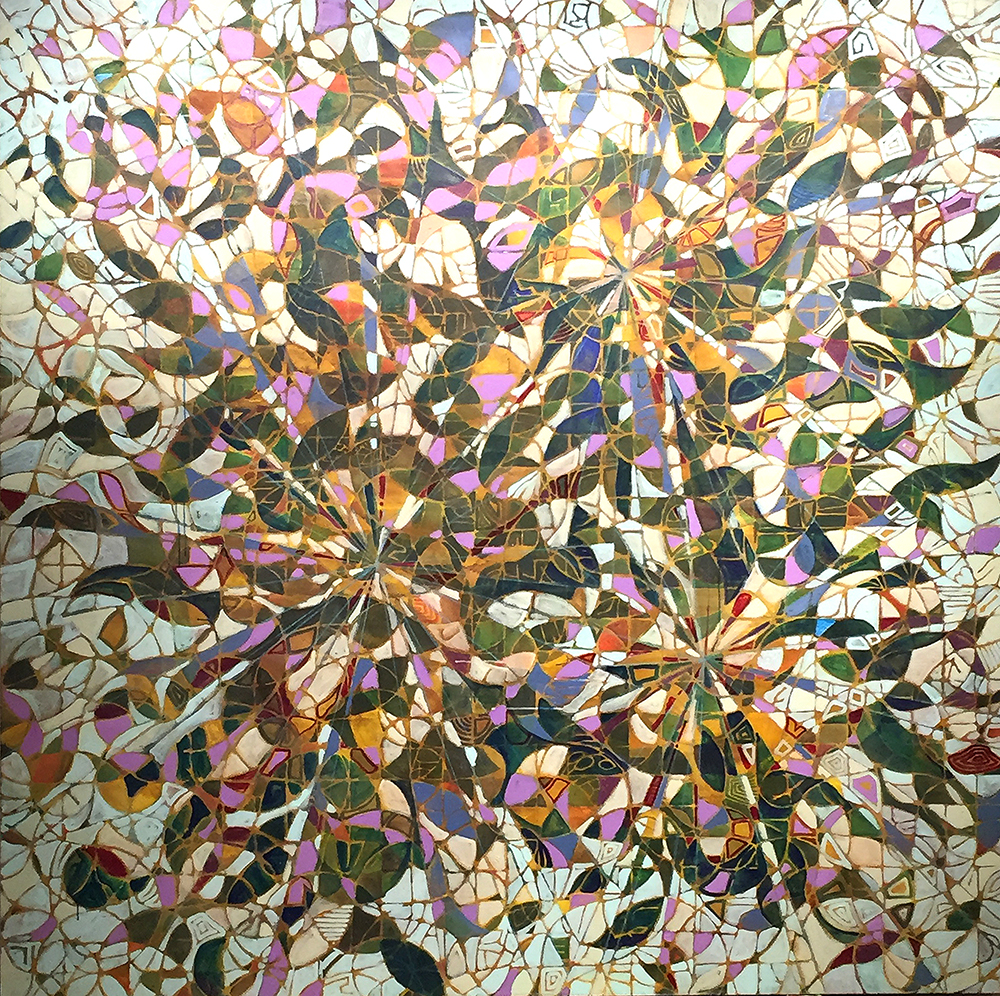

one by one by one

(in progress, detail 1)

And, accept it for what it is. In life sometimes we crave those blissful moments. But, I’ve learned to embrace those tender, hard, sad times as well. When you are open to seeing something for what it is, it leads to a more authentic, fuller life.

K: Right. You speak of bliss. How many times have you been in the studio, where the moments are truly at this high level. It’s so few. You might have a really good day, and the rest are pretty mundane. It’s these chopping wood, fetching water moments that build an artistic life. It is work. It’s a four letter word.

one by one by one

(in progress, detail 2)

I think that is largely misunderstood. They think artists have fun all the time.

K: My notion of the word “fun,” as it pertains to art, is one I continually had to explain to my students. If they said they were having fun, I would tell them not to use the “F” word in class. This would always get their attention. They would ask, “How can art NOT be fun?” And of course, it can be. There are times of joy and excitement. But if you are a true, practicing, authentic artist, there are few, fun days. Once you have that first, brilliant, beautiful idea, your time is involved with developing and actualizing it.

Paula Scher, a leading graphic designer who works for Pentagram, speaks about the importance of keeping the integrity of the original idea. After you show a client the the initial idea, they may love it, but have some changes. Suddenly, the idea washes down. As the lead designer, you have to corral them to stay up to a certain point of acceptance to keep the concept in tact. It’s never as high as the original idea.

It’s like that in my studio. I have to trust the process. I have to trust that this is all going to come to a point that honors the original idea. It’s messy. It takes time. You pull it all together, and then, you have to sit with it. So then there’s that curating time that we’ve talked about in other conversations. The detritus, the dust, has to settle, so then we can clearly see what the next question is going to be.

one by one by one

(in progress, detail 3)

And then, it seems discernment has to come in to play, and ask, “When does the time for this work stop? When is it complete?”

K: I do not consider my work to ever be finished. They just come to a stopping point. Just like my most recent exhibit, “order in an unruly zoo,” where even though each painting is separated by a white wall, or its own dimensions, I still see all of the work interwoven, like a Venn diagram. Each one overlaps the next, and the only time they will be finished is when I die. But even that is still not the final moment. Works of art are constantly dying. Because the materials are physical. We can not preserve art in perpetuity. The best example of this is “The Last Supper.” It has lost so much pigment from the nature of the material, and to water damage at some point. So now, what we really have is a reproduction due to the restoration process. When you restore a painting and you remove varnish, you are also removing part of that pigment. The best restorers know how to do this in the least invasive way.

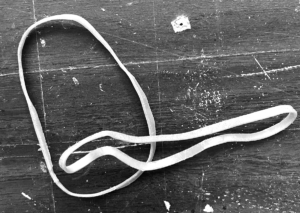

Also think of Eva Hesse. All of the pieces she did with fabric and resin are now so brittle, they can’t even take them out of the boxes anymore. I was using an old rubberband the other day and thought of her. It was hard and decaying. It will disappear some day. It’s matter. We’re matter.

Also think of Eva Hesse. All of the pieces she did with fabric and resin are now so brittle, they can’t even take them out of the boxes anymore. I was using an old rubberband the other day and thought of her. It was hard and decaying. It will disappear some day. It’s matter. We’re matter.

one by one by one

(in progress, detail 4)

If you were to create a Venn diagram of time for one of your pieces, what components would it be comprised of, and where would they intersect?

If you were to create a Venn diagram of time for one of your pieces, what components would it be comprised of, and where would they intersect?

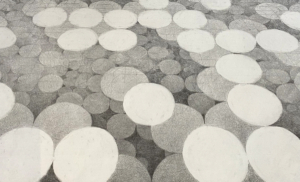

K: {laughs} Well, I think it would look something like this. Each one of these circles would be transparent, seeing through one another, showing different levels. Because it’s not just two objects, right? It would be as if you are constantly seeing through them all, and the Venn diagram is multi-dimensional.

one by one by one

(in progress, detail 5)

We talk about thought processes that zig zag. That zig zag is not even on a flat plane. It’s changing altitude, while changing attitude.

one by one by one

(in progress, detail 6)

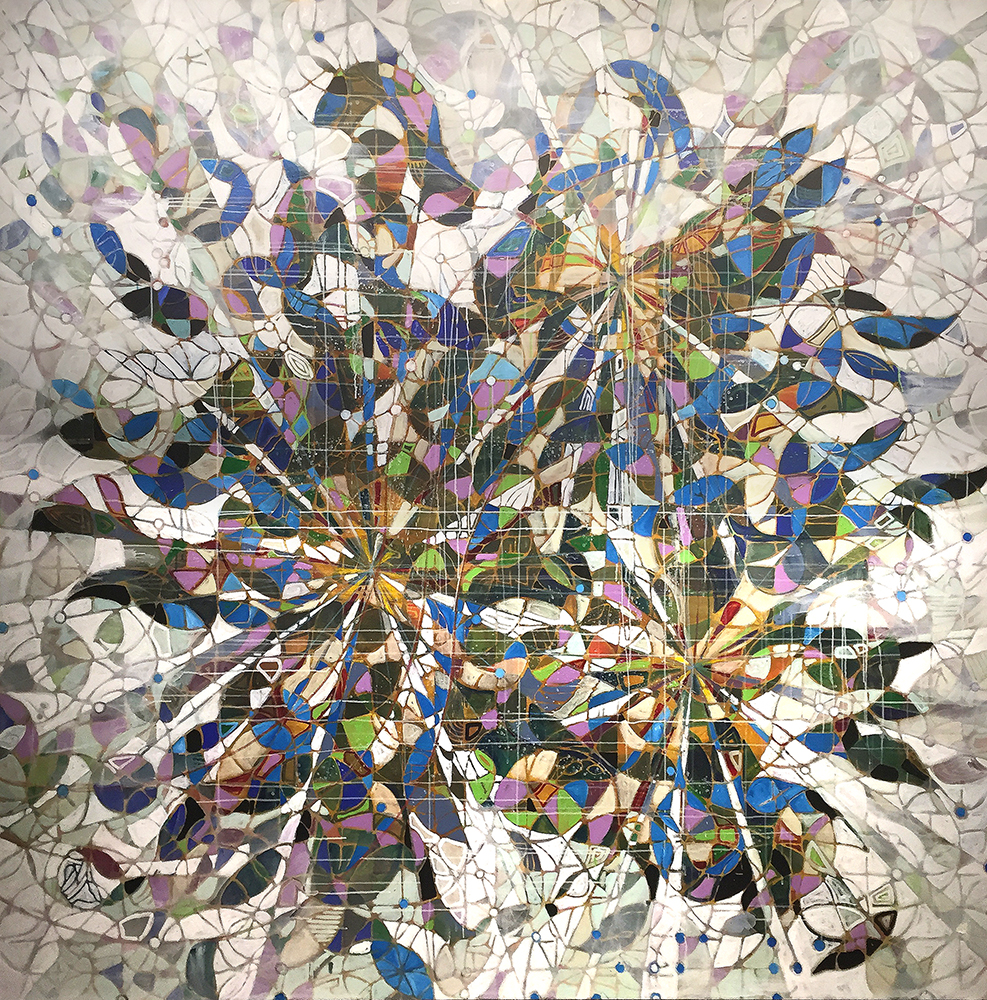

And just like your work that is never finished, it seems like we could infinitely talk about the meaning of time. For now, let’s pause this conversation and end with the final image (or, stopping point, as you would say) for “one by one by one” – that illustrates the conceptual development, experimental, and physical time that comprise one of your pieces.

one by one by one

2020, mixed media on on canvas, 96×96 inches. Collection Trammell Crow Company, Twelve 24, Atlanta, GA