In this conversation, Kenn leads us through his journey of discovering a component he first added to his work about 10 years ago, Braille. This new language and aesthetic not only brought mindful depth to his art, but also posed questions, brought up new vulnerabilities, and formed new community connections to Kenn’s life, as one day he literally walked in the footsteps of those that experience blindness.

{If you would like to decipher the Braille titles as you read, please click here for a translator. You may also click on a title to see an instant translation, or see the translated list at the end of the conversation.}

CONVERSATION.11

When did you first discover the idea of incorporating Braille into your work?

K: It all began one night about 12 years ago. I was up late researching. Being at a crossroads in the work, I was looking for something – but didn’t know what – and I just happened upon Braille. Its geometry and symbols for language deeply resonated with the geometric vocabulary in my work, as well as my expertise with typography as a graphic designer. It seemed like the perfect fit.

The deeper I went into researching, these light bulbs kept going off. I found that each of its letter forms is called a “cell.” So there was cellular geometry, the build up of form, mass and ideas through these signs.

What were you working on at the time?

K: I was working on rectilinear pieces. And I had just begun to do circulinear pieces. I wasn’t even contemplating the third-dimension yet. As a graphic designer, I was working in two-dimension within print publishing. Every now and then we had a job or project that we could do bas relief printing, or raised surfaces.

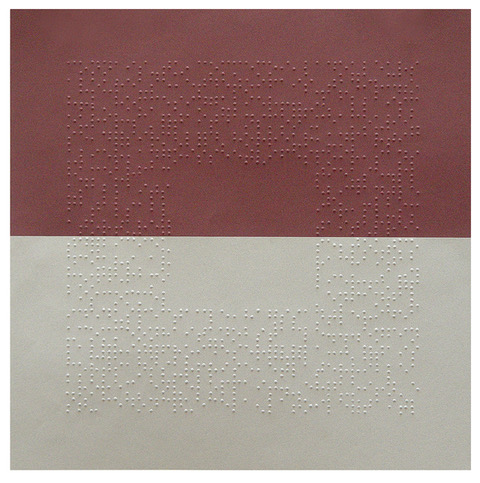

deep by deep

mixed media on canvas

K: So that’s why I was on that strata, skating on that surface of 2-D when I happened upon the whole idea of Braille. I started to research how Braille first came about. I knew about Louis Braille, and that as a child he was blind. But I learned that he was actually born with sight. When he was three, an accident in his father’s workshop injured one of his eyes. It later became infected, and then affected his other eye, leaving him permanently blind. After this, his parents put him into a special school.

While he was at this school, Charles Barbier de la Serre came to speak about a system he had devised. He was a former general for Napoleon’s army, so had witnessed that at nighttime, his platoons lit fires when they had to see something. Of course, if he could see this, so too, could the enemy. To protect his men, he devised a code system of raised dots that he entitled, “écriture nocturne,” or “night reading.”

It was a much more complex system where each cell was 12 dots. When Barbier brought this system to Louis Braille’s school, Louis recognized that it could be simplified. It took him several years to develop, but he eventually created a 6-dot system. Louis was only a young teenager at that time, and it wasn’t until after he died that the strength of his system was appreciated and largely adopted. But now, almost 200 years after he developed his system, it still remains the universal writing and reading language for the blind all over the world.

How did you first incorporate Braille into your work?

K: Some of the first pieces I did were installations based on the “écriture nocturne.” They were raised dots on the floor that I painted with florescent paints, and illuminated them with blacklights so they would glow.

écriture nocturne – night writing

K: This idea of seeing in the dark truly opened up so many different ideas to explore. It’s interesting to look back on this series of work, and try to piece together its lineage.

First, there was the component of exchanging ideas through code. Our society is replete with differing codes. Sometimes we even speak in code to one another. There are codes that also run our technologies and softwares.

Also, when we disseminate information, we tend to be guarded. I began to recognize that secret coding has been part of society since the first time we had a disagreement with another party. How do you send information so that the other party doesn’t know what you are doing, so they can not see? It led me to think about secret codes, codes by which we live by, dress codes, norms, … and on and on.

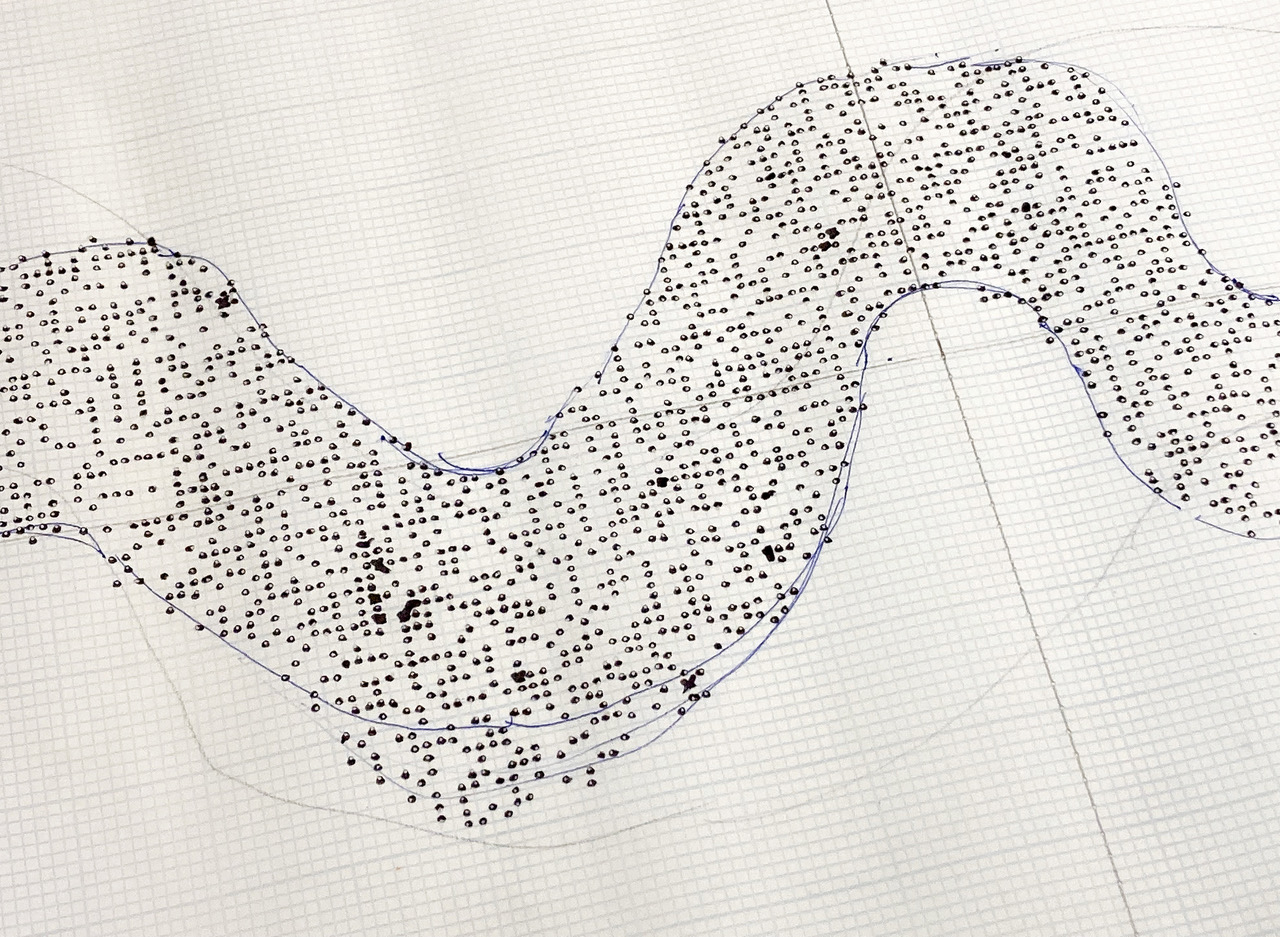

It became this anthropological study of environmental culture, but also humanistic culture. And then I began to wonder, “Why am I only stuck in the two-dimension, when Braille’s intent, by relief, is three dimensional?” So, in an experiment, with a hammer and nail punch, I laid out a grid on paper and started embossing it. I would first write in Braille what I wanted, flip it over, punch it, then turn it back over and there was my Braille.

Did you use the same scale that was developed by Louis Braille?

K: No, I did not. I started larger because the nail punch I had was based on a quarter inch grid. The cell was a quarter inch wide by a half inch tall, which is too large for what is considered Braille. Braille has two sizes, both of which fit within the average fingertip.

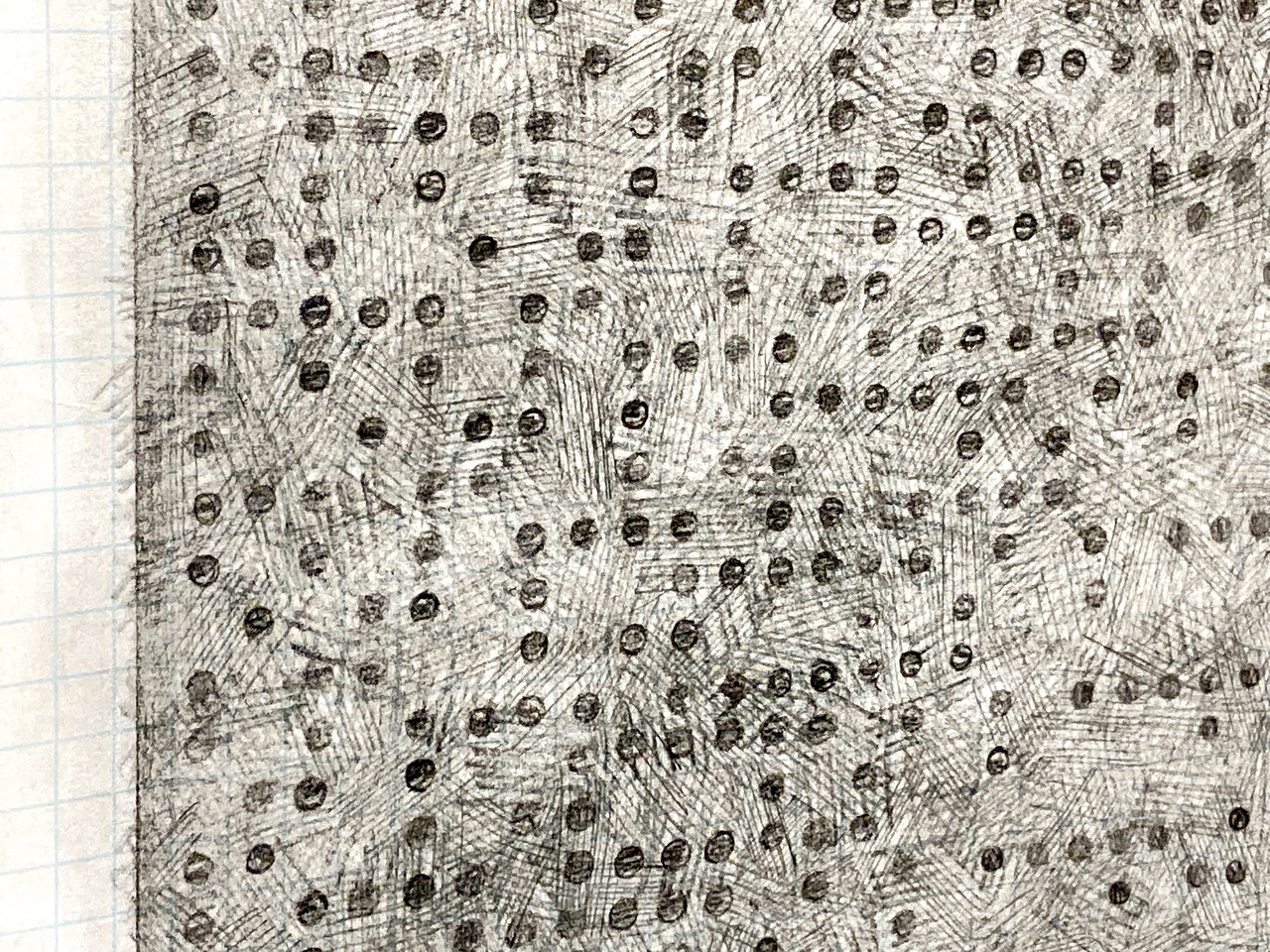

My first explorations were based off of the tools I had in the studio, along with what I knew of the orthogonal grid, I was well-versed through architecture, and even graphic design. I could see that cellular geometry has a definite relationship to the grid. When I was laying my Braille, I was thinking of its patterning. I enjoyed the patterns that all of those letters created.

copper study

How did it feel to go into the third dimension for the first time with your Braille pieces?

K: Oh, it was an exciting day. It also simplified the content within that particular piece. Because with everything else, I had been layering lines and color onto one another, where this, I could just punch out content on a green piece of paper. This gave me a channel to express not only my respect, but my love for minimalism.

It is interesting to hear the switch from when you were painting, you were obviously working on the front of the canvas, to Braille, which moved you to working on the back of the piece. With this, you can’t appreciate what you’ve done until you flip it over.

K: And to further speak to this, when I bought my first stylus and slate {the stylus is the little punch piece, and the slate is the metal grid that you slide the paper in between}, I mistakenly stated that when using a slate & stylus, blind people wrote ‘backwards’ and was then corrected upon speaking to someone at the Federation of the Blind, that blind people write in ‘reverse.’ That was one of those moments that I was contemplating that if we as a society all had to that, we would still be dragging our knuckles, hitting flint rocks together.

I am imagining that due to the complexity of the way their information is disseminated, does it make the it sacred to them in a way?

K: Yes, so unfortunately because of this, in the visually-impaired/blind community, there is a higher level of illiteracy. It is so difficult because first you learn how to read Braille, and then you have to learn how to write this language in the opposite way. Our brains are not necessarily wired for that.

Can you walk us through your process of these first Braille pieces?

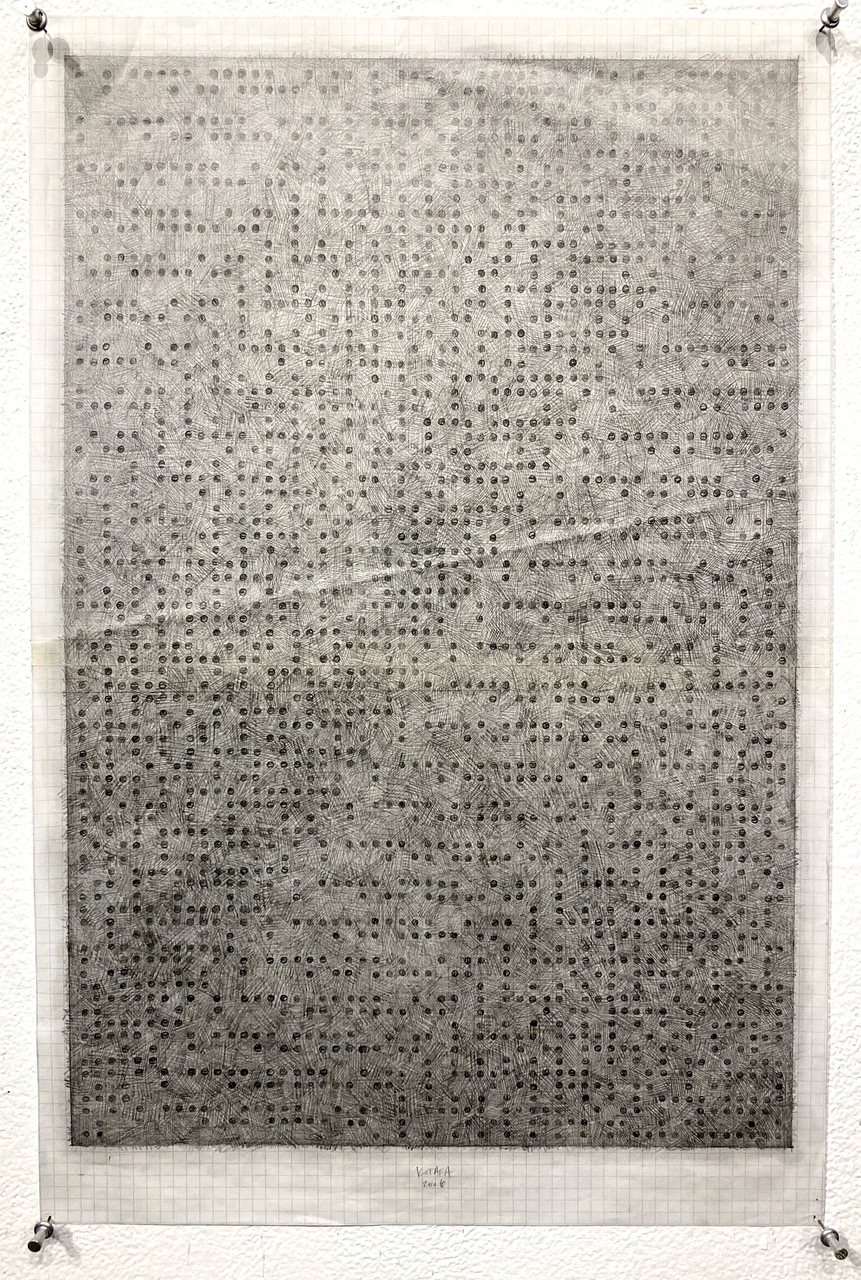

K: Sure. The first pieces I did were on gridded paper because I had to bridge that spatial organization to fully begin to comprehend this. I used grid paper and marker, writing, or laying out dots as they are seen. The sheet of gridded paper was turned over revealing the marker dots in reverse. It was placed on paper and hammered, with nail punch. Upon completion of hammering, the gridded paper was removed and the paper turned over to reveal Braille.

{Kenn shows me a Braille piece where the grid has been drawn in perspective.}

and I stayed waiting still

punched Braille on paper

untitled-braille alphabet

pencil on paper

untitled detail

grid paper with Braille

This is fascinating because of course, the audience for your work is primarily sighted, so the Braille takes on a different context than its original purpose, as language.

K: Yes. And, think about the inherent codes in any work of art. The artist is privy to the work’s principles, and vocabulary terms. But for the viewer that isn’t artistic, oftentimes, it is a foreign language. And I recognize that.

It is so interesting to think of the sighted people that are viewing the work. For them, they’re grasping composition, color, and all of the visual, artistic elements. But the blind person, is looking at the information, the content within your work. I love how you have included both audiences, and that they are experiencing your work from two, totally different perspectives.

K: And then it becomes all about human interaction. We now know that for sighted people, 60% of all information we take in is through vision. And then the next highest percent (20%) is through hearing. For the blind, it’s flipped. It’s that one touch that is high on their priority, but so too is audio. With new technologies, many blind people are educated through audio. Braille is such a difficult system to comprehend, especially because we also do not have an education system to administer those pedogogical ideas.

With voice-to-text technologies and the ever-increasing availability of audio books – what is the longevity of Braille?

K: I would think that Braille printing is probably on the same trajectory as traditional printing.

So your art also serves as an archive.

K: I guess it could be considered an archive, but it’s also a connection to a group of people that are different than I am. It gives me an understanding and appreciation, and maybe it’s like learning a foreign language. You understand different ways and means of expressing ideas and communicate those ideas and concepts.

When you first created these works, I’m curious about where they were first exhibited? When did they get introduced to the blind community? And, what was that process?

K: One of the first pieces I transcribed was Abraham Lincoln’s, “Emancipation Proclamation.” I was thinking within minimalistic constraints: blocks of color, and the meaning behind them. When I took the “Emancipation Proclamation” I began thinking of generic, racial descriptions: black, white, red, yellow, brown. So, that piece was a stratum of these colors from dark to light. At one point in the proclamation it says, “In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed” Of course what Lincoln was doing was attempting to end slavery. And what that document stands for is that we are all equal here. Of course, this is not yet an actualized reality. A document alone does not change society. People do.

have here unto set these hands – emancipation proclamation

K: But this abstraction of idea became this clandestine maneuver to present historical information, whether it was literary, poetry, politics, or even pop-culture quotes, put them out there, and see how the public responded to this.

After putting a couple of pieces out to the public, there were a couple of people who recognized what this work was speaking to. One was John McKibbon, the owner of the Aloft hotel chain. Because he was in the hospitality industry, we had a lengthy conversation of what he envisioned for the language. He asked if we could we use quotes and language on “the journey” or “travel.”

the travelers

Aloft Hotel, Asheville

K: So I came up with ten quotes on travel. Everyone from Greek antiquities, to one with Steve Martin, and all points in between. It’s a very minimalistic piece, with a black backdrop and copper furniture nails. And, once again, it added one more level of connectivity because here in North Carolina we used to be known for our furniture production, which has now vastly moved overseas. I found a company in Hickory that sold several different types of furniture nails. I was like a kid in a candy store, settled on 1/2” copper nails, and bought them all up.

I appreciated that John McKibbon was willing to push and challenge folks at his hotel because he placed the piece in the stairwell, walking up to the check-in. He then had the great idea of how to incorporate this into the community. He offered to donate $1,000 for each quote to charities to be named. We focussed on the Literary Council for the City of Asheville, and the Industries for the Blind (IFB). What was so nice about this was that John loves driving community participation. He did a huge PR event, with the television news, and he presented $5,000 checks to both the Literary Council and the IFB.

K: It was there that I met the Program Director for the IFB (the local Industries for the Blind). What the IFB does, is they hire blind and visually impaired people for a living wage to work. They give them tasks that they can feel their way through.

He asked if I would like to conduct a class to work with blind people to teach art. I immediately jumped at the opportunity. We met once a month for a year. I volunteered my services on Saturday mornings. At first we worked with clay that you could fire in the oven. We would talk about form, shape, and so on. We began to work with different materials that we could manipulate. Eventually I was running out of ideas, so I asked them what they wanted to do. Someone asked, “Can we create something in origami?” And I confidently said, “Yes! Let’s do that!”

Well, I got back home. {laughing} And thought, “HOW am I going to teach a non-sighted person origami?!”

Right. Figuring out and then languaging all the points of reference to walk them through such a complicated process!

K: So I mapped out the idea with ratios and proportions. So I took some paper and asked, “Can you find a third in this piece of paper? Okay, now, find a half, …”

Did you close your eyes to test your process?

K: Yes! I’m trying to close my eyes, and I think I was even working with my son, Julian at the time who would have been, maybe 12. Because my brain is so well-formed for visual elements, almost concretized, I had to get beyond that, and find someone who is not so conditioned.

So, we got into the studio and we made the basic swan. They ate that up! And I was welling up …

Did you cry?

K: Almost.

Yes. I can imagine that would be pretty moving. To give the gift of art to a new group of students after teaching all of those years.

K: Through this program, I met a representative from their Winston-Salem office. She asked if I wanted to participate in a day-long seminar where sighted people come in, put on blinders, and go through steps, events and processes that the blind do on a daily basis. We poured water into a glass, where you would place your finger in the glass as a reference point. We learned about money, discerning between the different coins, and the challenges with paper bills. They have a folding system to differentiate between the denominations.

The most difficult part: in their complex, they house a cafeteria for the workers. With a walking stick, we had to make our way through the building, find the cafeteria, order food, pay for it with cash, check your change, and then take the tray of food with your walking stick, find your table …

Did anyone drop their food?

K: No, surprisingly. Then we ate, and then put our tray back. So once again, we take all of these for granted.

How did you process the feeling you may have had, of being so exposed with the blind fold on?

K: Vulnerable. I had to trust like never before. We also spoke about money, and getting change. With their folding system, they knew what bills to use for paying, but when you received change, you had to trust that you were getting the right amount.

I’m wondering for people with sight, is it easier to be a cynic because we are more hyper-independent? Do blind people see the good in people because they have to trust? We don’t have to trust in that way.

K: I’ve learned that the breakdown is probably similar to sighted people. But, I did find most people at the IFB to have a positive nature. And, some studies have shown that giving sight to someone that was blind is not necessarily a gift. One instance, a man named Dr. Moreau restored the sight to a young man. Instead of being helpful, the young man found this new sense to be overwhelming, confusing, and eventually wished to go back to being blind. Moreau says, “The sober truth remains that vision requires far more than a functioning physical organ. Without an inner light, without a formative visual imagination, we are blind,” he explains. That “inner light” – the light of the mind – must flow into and marry with the light of nature to bring forth a world.”

K: In many ways, the idea of working with Braille has led me to the notion of we consider “perfect” and “imperfect,” “philosophical,” and “ideologies.” I’m right, you’re wrong. I’m perfect. You’re imperfect. It led to me so many different areas of personal study and personal growth. I want to remain more on the positive side of all of this. And, I’m still striving for that.

By working with the IFB, and putting the work online, it is garnering attention. A contemporary museum in Arizona found me online. We’re putting an exhibition together on “text.” I shipped some of my work, but I also wanted something that people could interact with and write messages in Braille. I created a 4’ x 4’ square metal bulletin board and color-coded magnets. The museum lasered a grid on the metal so people could write messages in Braille. What a great way for people to touch the artwork and be a part of the creation.

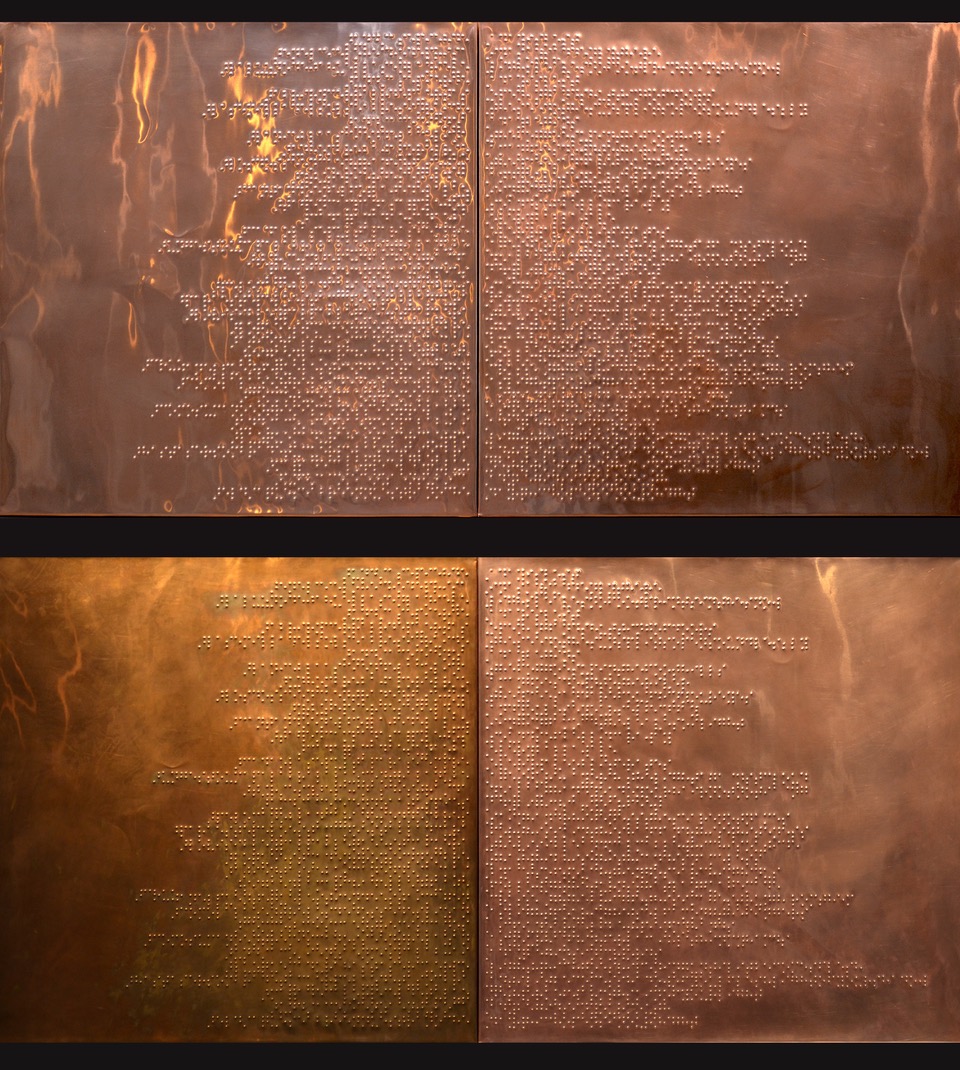

Many museums have programs that bring blind people in to feel the sculptures. But they can’t go up and feel a Çezanne, or a DeKooning. For one, the people could hurt themselves, and it could also damage the work. I like the idea of putting artwork in that someone can touch. I’ve been very fortunate to participate in several exhibitions like this. This focus led me to think beyond imprinting Braille on paper and ask, “What materials are best suited for human interaction?” Metal became a great solution. And copper with its patina effect the more the surface is touched. But it is also, in its softness is so accepting of contaminants that are airborne, but particularly to touch. The oils on our skin change the surface.

So, copper becomes this narrative. One of the first pieces I really enjoyed doing used a poem by the Mexican poet Octavio Paz. It was a diptych, where the left side was in Spanish and the right side was in English. During the three months it was exhibited, I instructed the art handlers to clean the English side once a week with a solution I gave them, and to not touch the Spanish side. When they asked why, I said, “How many times as Americans, do we look at other countries and see their old, antiquated buildings and art and think how beautiful it is? We’re so admiring of other countries for their history. We call an antique here as something that is more than 30 – 50 years old. They are talking hundreds, if not thousands of years.” I wanted the patina to show a visual differentiation between the languages.

Un día comienza – A day begins

early stage and later stage with patina left panel

K: Ultimately thought, I want people to begin to recognize some of the similar growth components that I have. Can this work trigger something within them and recalibrate their ideas and notions of other people who are different from them. And shift them to a better place. That’s why I continue to work with this. I find it very challenging, and hopefully this upcoming exhibit will touch upon this even further.

K: The exhibit is called “the deepest soundings.” This is about surface and depth. On the superficial level, people can recognize that it is Braille. But, the work invites you to dive deeper into the insights of the content. So, as we talked about trust before, here, if they choose not to decipher the Braille, the viewer is trusting in me that what I say its meaning is is true.

Do you give people a decoding alphabet?

K: I do. I also place one on the back of collector’s work so they have a reference when they take the work home in case they ever want to go through that process of deciphering it. So, “the deepest soundings” is looking at your first initial reactions. The extended experience is moving beyond that factual, evidential surface. Sitting with it long enough to gain insight into the content and what it means to them. In this work, I’m working with all of these metallic, shiny objects, using the idea of wanting attract the moths to the light. As humans, we are attracted to shiny objects because we often perceive them as having greater value. And then the question arises, “Is this value real?” Then, is that value equated with that viewer. The gold is fake, it’s metallic paper. The paint is fake, but still, its glow draws them in. It leaves one asking, “What does this actually mean?”

“the deepest soundings”

solo exhibition of Braille based work investigating language as value at ‘Fringe: an art experience,’ Ruston, LA

Oct. 1-29 Reception October 1, 4-6 pm

CONVERSATION.11 : braille work

“The only thing worse than being blind, is having sight but no vision.” ~ Helen Keller

[1] THE ORIGIN OF BRAILLE

[2] A BUDDING IDEA

[3] FIRST EXPLORATIONS

[4] LEARNING A NEW WAY

[5] CONNECTING THE DOTS

[6] A CHANCE TO TEACH

[7] A CHANCE TO LEARN

[8] INVITING INTERACTION

[9] LIKE MOTHS TO LIGHT