Art as a vehicle of awareness has the power to unveil truths. Sometimes it reveals all that is beautiful, and other times, what has been lost. But always, it is asking something of us. And usually, it is to expand beyond what we know into a new realm of possibility and deeper meaning.

Throughout this conversation, you will find some of Kenn’s quietest work. We invite you to use each one as an opportunity to pause, be silent, and feel the presence of the moment.

CONVERSATION.12

“I think I will do nothing for a long time but listen, and accrue what I hear into myself … and let sound contribute toward me.” ~ WALT WHITMAN, Leaves Of Grass

What does listening mean to you?

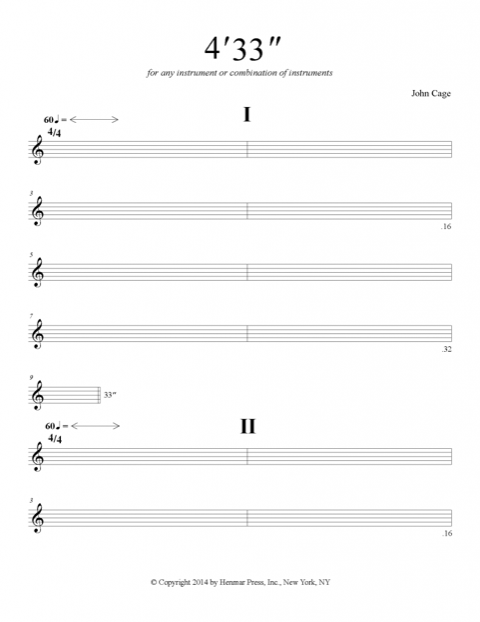

K: The first thing that popped into my mind was the John Cage music piece. “4’33”.” He came out on stage to a piano, and just sat there.

Did he have his hands up on the keys?

K: No, I think he just sat there. The audience started fidgeting and rustling. And, this is exactly what his intent was. Listening, silence, and the ambient noises. That’s really genius.

Score for John Cage 4:33

Right. The performance becomes the sounds of the audience.

K: It really responds and connects to how often do we actually listen. In our contemporary society, it is noisy, and cacophonous. As Westerners, we are compelled to fill every negative and quiet space. This reminds me of a story about when one of my best friends took his young teenage kids on a trip out West. They were driving along, kids were on their iPads and phones. All of a sudden he stops and says, “Kids, get out of the car, now!” Everyone gets out and he says, “Listen to this.” It’s dead quiet, with just the rustling of the wind through the fields of corn. The kids are disorientated, and are looking around asking, “What? We don’t hear anything.” “Exactly,” he says.

We as a society don’t know how to listen and be quiet.

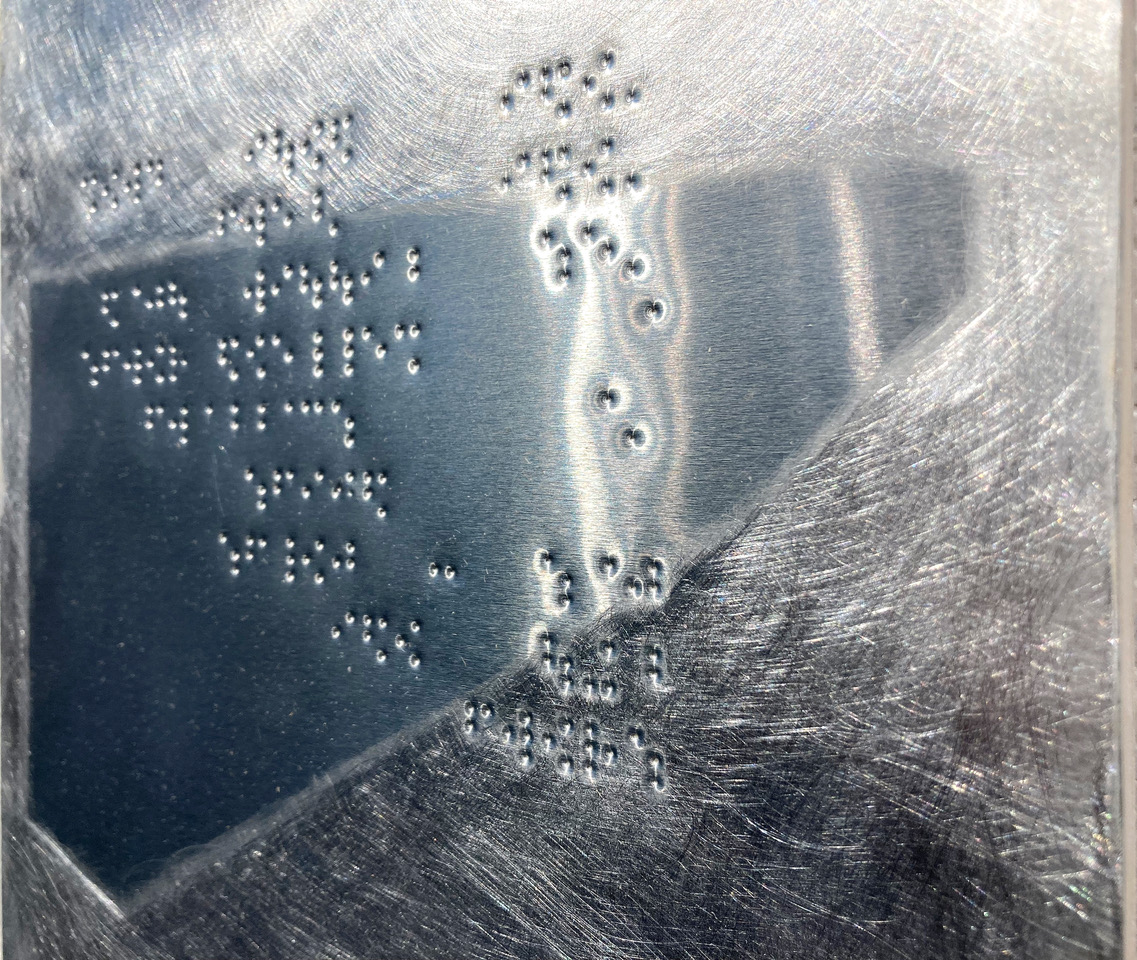

__o__ detail

2022, braille on brushed aluminum, 10×8 (transcribed from Emily Dickinson’s “Gorgeous Nothings”)

With this first pause, a note from Kenn:

“We live in a society of sound whereas noise pollution is commonplace, necessary even. My reaction to this is very much a needed time to unplug and seek silence. It becomes selective listening. That in turn has produced quiet pieces attuned to listening to my own body. Two recent braille based, brushed aluminum pieces seek just that by inverting the Braille dots. Eraser is similar to silence in that something can be removed but a palimpsest still remains.”

And when we are listening to someone, our minds often hold an expectation of what we intend to hear. How many times when we are listening to someone do we focus more on what we want to say, verses absorbing what they are trying to convey.

K: Right. It becomes almost more a form of entertainment. We struggle to sit back and listen to someone and have the need to respond and fire back. I think that’s the root of this constant sound. We’re not well-equipped to listen. When we can sit back, and just take in what we are hearing, and delay the reflex to expound upon, argue, retaliate, or to put in our “two cents,” this is when we truly hear.

It is a lost art of reciprocation.

K: Indeed. It feels like what we are more into now is a volley.

And, the pre-programmed responses.

K: Absolutely. We are automatically loaded with responses. Because, how many times have you had a conversation with a person, and even before you finish your sentence, they have a response, and can’t wait to get it out!

{both laughing}

Yes. It’s that longing to be heard. Everyone wants to be seen, loved and heard, but there’s an opportunity to let that urge be and not let it interject and take over what’s happening.

K: We don’t fully listen. We pick up on and latch onto key words or phrases when someone says something.

_i_e__e.02

2022, braille on brushed aluminum, 10×8 (transcribed from Eugen Gomringer poem “silencio”)

In your practice and your teaching, you always start with the essential process of defining the vocabulary around what you are doing, so you are not assuming anything. It is a deep form of listening. Like Walt Whitman describes looking at things with “fresh eyes,” so too, you are listening with “fresh ears.”

Typically, when we hear a word, we have an instant trigger, a definition for it. We lose context sometimes when we do this while we are listening to someone. It’s like we listen as if we already understand.

K: In my experience with students while teaching “Graphic Communications,” I tried to always convey that a good designer has to be a good listener. The entire process is predicated on a designer listening to another person impart their information, accept that information, and to filter back in accordance with the client. And so, I would become frustrated when I would throw out a project and within 10 or 15 minutes, I would have students announce, “I have an idea.” I would respond, “You have already missed the point. You may have an idea. Set it aside, and start the process of first assessing what do you really know about this project? What research have you already done in 15 minutes where you can tell me the problem is solved?” Oftentimes I would say, “You’re not listening, to your own self. All you are wanting to do is get this over with. Boom. Done.”

Right now this is a critical situation. Within social media, we have spin doctors that take a couple of words or phrases and throw it back into the opponent’s face. We almost have to position ourselves better than the original content. So we are not listening. It is a sort of battlefield of “us” verses “them.” When we begin to remove ourselves from other people and get within these enclosed tribes, it creates a perpetual duality. This is where communication will only continue to break down further.

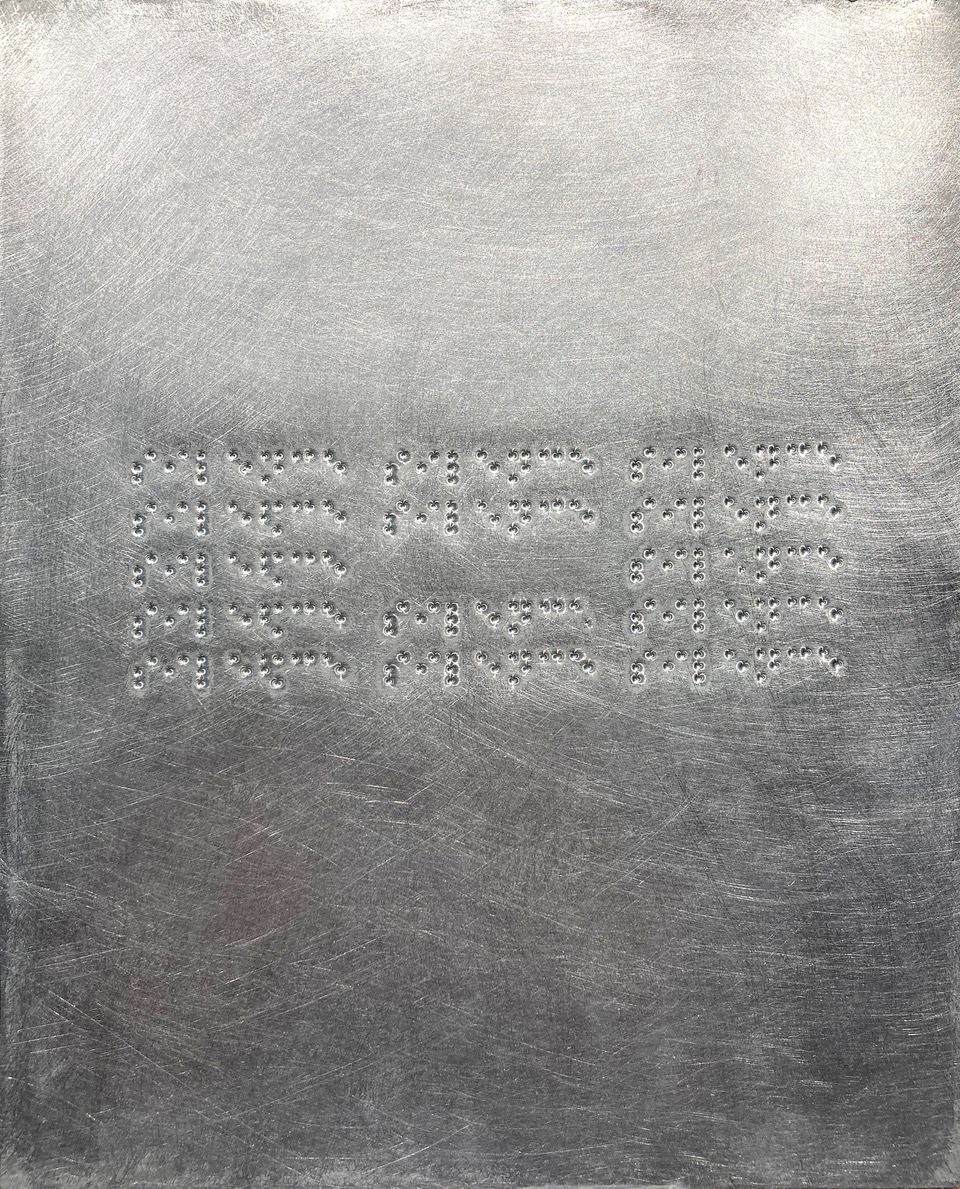

barbe espagnole 60

2021, acrylic on canvas, 77×51

I have two curiosities: One is, “What part does ‘listening’ come into play when you exhibit your work?” And two, “What is your process of listening as you are creating?”

K: These are two excellent points. Maybe I should speak to the studio process, the creative process first because I now work in silence. Every now and then if I have a studio assistant working with me I might play music. But when I’m alone, I don’t want those other sounds. I don’t want other senses polluting my own thought processes. I’m trying to figure out my own synapses, and when music is brought in, it just becomes a distraction.

I specifically can’t do it when I’m punching Braille, especially if I am punching Braille in reverse.

Now in my practice, I am at a point where I am unravelling 62 years of this buffet of existence. I am asking, “What have I taken in?” I really want to be conscientious and in that moment where I’m not affected by other stimuli. So that’s why I don’t play music anymore.

When inviting listening into exhibiting the work, especially at an opening, the majority of openings unfortunately, have been less than optimal. When I go to an opening to see someone’s work, I want to speak to them about their work and process, materials, and so on. One of my pet peeves is when someone comes up to me at one of my openings, and wants to talk about their work. I have tried to be patient with this and listen, but I have come to the point where I might say, “Excuse me, but where is your work now? Is it here? Why do you want to talk about your work? Do you not want to know about mine?” This will of course ruffle their feathers. But sometimes when the person goes into a singular-focussed conversation of “me, me, me, I, I, I, …” I will just kindly excuse myself.

The recent exhibit at the Black Mountain Center for the Arts, I would say, was probably one of the best receptions I have ever had. For two hours, everyone there wanted to talk about the work. They did not flip the conversation to be about themselves. It is not that I am solely narcissistic – although there is a bit of narcissism in any art practice. But I enjoyed other people’s input and questions about the show. They would tell me what they saw, and then ask what my intent was, or what materials I used. Those are quality questions.

I know very well that once the work leaves the studio, it’s not really about me anymore.

barbe espagnole 66.05

2021, pastel on paper, 40×26

Well, the work is doing its job in that instance. When there is an opening, and other artists come to network, let’s say, that’s not what that exhibit is about. It’s about the work, and you created the work, so you are the go-to person to ask about it.

K: Right. At an exhibit, I am wondering, are they listening to the work? We metaphorically transpose senses all the time, right? We use the term vocabulary: “What is your vocabulary as an artist?” Well, vocabulary is a textual, literary term. Do you listen to the work?

I am watching a documentary about Chinese work. In this, they say, “We read a painting.” So I love the way we shift and change senses. But ultimately, are we present, are we listening, are we seeing, are we connecting to the work?

You are an artist creating work, obviously. But the people that come to the exhibit can be from all walks of life: a lawyer who has never drawn a thing; a doctor, who perhaps is a surgeon, so their hand-eye coordination is highly developed. Even though they are not an artist, maybe they appreciate the mechanics of what you have created.

K: I think it’s interesting that you chose attorneys and doctors. In a good number of sales of mine in the past – especially the curvilinear pieces – have been collected by people in these professions. Because these pieces are so structural, and there is a sense of order within chaos. Those two professions are very reliant upon the black and white interpretation of the events in their lives.

I was just thinking about whoever comes to an exhibit is bringing their own library, language, and they are using that to perceive. There’s that interplay between their own experience and what they see.

K: But they are listening to their own, internal library. We each bring our own experiences and knowledge, but these things can also change daily. We are never the same person day in and day out. Of course we are in a general sense, but moods change. How much sleep did we get? How much coffee did we have? Maybe at an opening, you’ve had too much wine to drink. And so suddenly, your perception is going to be changing, but maybe – you listen, you see better with that.

In one of the books I’m reading about surface and depth, the author is writing about the history of written communication and oral communication. The ancient Greeks did not like written text. They thought the oral presentation was the pinnacle of communication. They thought that written text was amoral, and even a sin, which is fascinating.

That is interesting, because now, some relationships are highly based on emails and texts. What is being interpreted? What is being lost? Did they have the sense that human interaction helped keep the message more pure?

K: Yes. They considered that the higher form of communication. But you are right, though, that these days, how siloed are we due to modern technologies? And, we’re not listening to one another: we’re just kind of firing back. Are we limited to how many characters we can post on Twitter? Or, are we limited to a 3 x 5 inch screen? What type of experience is that?

When I hear someone who articulates and speaks eloquently, and shapes it into this catching, magnetic narrative – I’m all theirs. I work at this myself, and finally feel like I am gaining clarity. It’s been 60 some years, it’s about damn time!

I think that’s why TED Talks were so popular for a while. There is this hunger to listen to ideas. And people who articulate these different ideas, like the Netflix program, “Most Unknown,” where one scientist visits another scientist from a very different practice and listens to what they are doing and tries to understand. It’s pure reciprocity.

Right. That program is magical to watch. When a genius scientist looks at the camera with confusion because they are trying to understand what the other scientist is teaching them. And then, the look of surprise from the scientist who has been explaining what they are doing, after hearing the fabulous questions from the scientist who has been listening. The inquiries are so fresh because they come from such a different perspective. It opens up new possibilities. Both scientist are so specialized, they spend much of their time with colleagues who share their expertise. They both walk away enriched and changed from that interaction.

phenom detail

2019, braille & clear coat on copper, 32×32

So, I guess I am curious, Kenn, what do you do to be a better listener? Do you have a practice of honing that skill?

K: Yes. And, let me start with a note that I am not always successful at it. It is a process, a practice. When I go into a conversation, I like taking that moment to take a breath. Part of my practice now is to be all encompassing – that meditative, contemplative component. Being a better listener, and less of a talker.

It makes me think of a quote by Matisse. He said, “You want to paint? First of all you must cut off your tongue because your decision takes away from you the right to express yourself with anything but your brush.” Let the work speak for itself.

That’s cool.

K: It is, but I don’t think it works anymore. During Matisse’s time, there were not the technological distractions we have today. Photography was in its infancy. That was the greatest technology. People still went to museums to view the newest ideas, and they were better versed and educated at looking at static images. Nowadays, I don’t think we are capable of sitting with a stagnate image that long.

Are we losing that value?

K: I would have to say, “Yes.” For a while, museums prohibited taking photographs. Now with the power that posts on social media can have to gain exposure, they allow them, merely to survive in this environment.

So the power that a piece of art once had when you stood before it, gets watered down by this. You have spoken a lot about this. You can Google anything. If you look up a painting on your phone and then say, “Okay, that’s enough, I’ve seen it now.” You are missing out on the whole experience, the value that piece has if you view it in person.

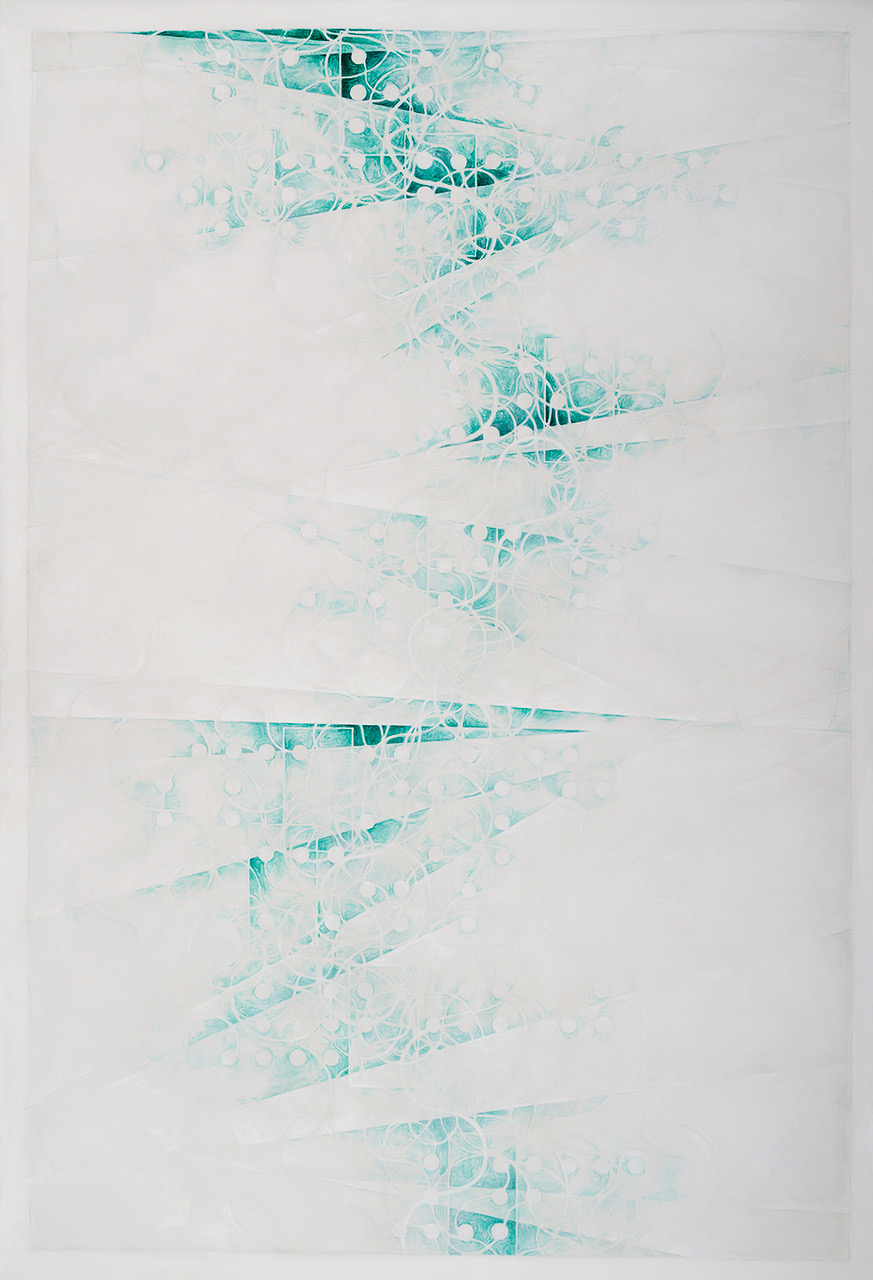

K: I don’t think they are listening to the rhythms and the heartbeat of the universe, of what emanates as we’re flying around in this mothership at how many thousands of miles per hour, circling around the sun. We’re losing those natural reverberations. And this is tied to much of my work right now: perfection/imperfection, losses/gains, and so on.

In many ways it’s frustrating. There’s a sadness to it. But really, it compels me to work more. And I know there are people out there who are hungry for this.

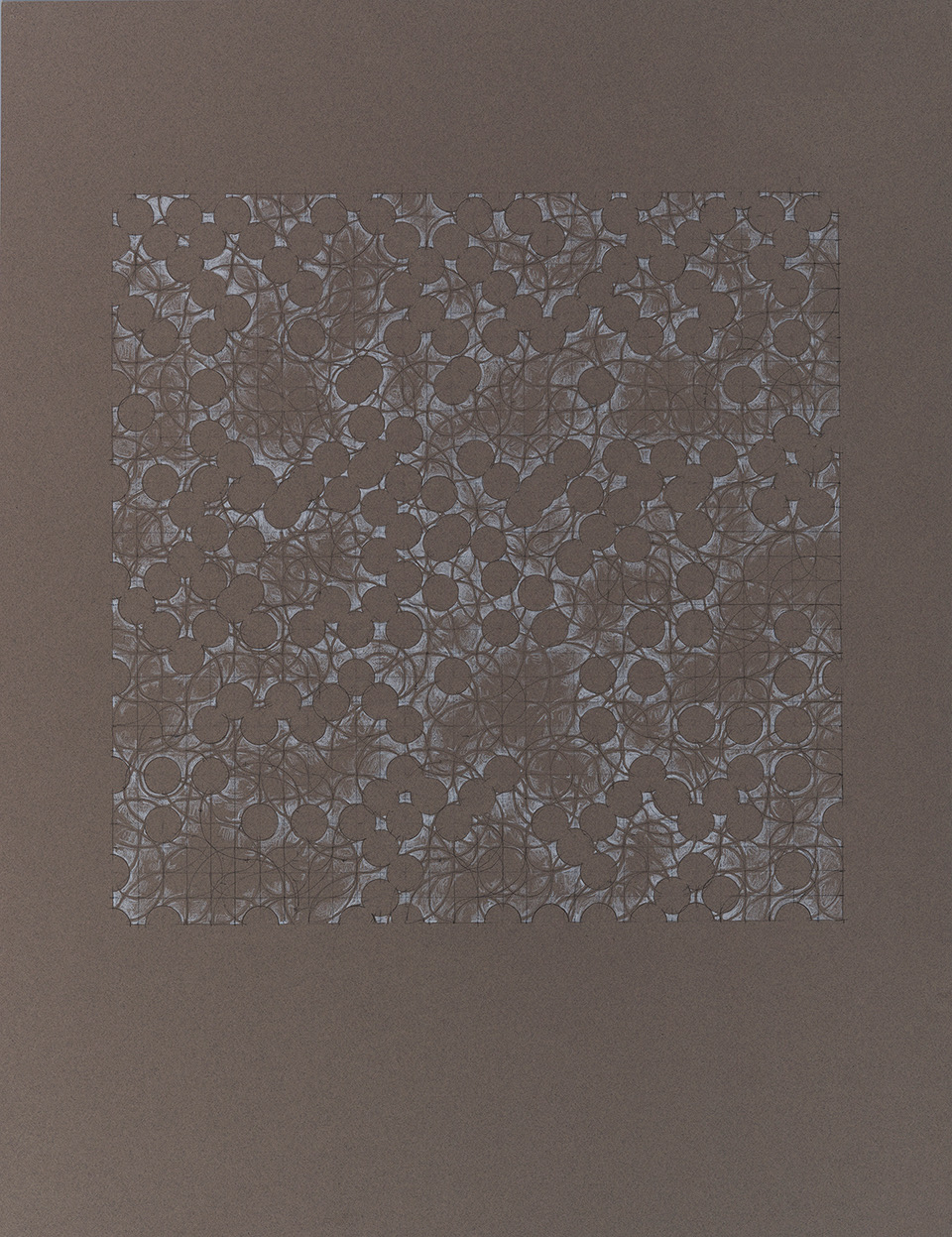

untitled_grey

2021, pencil & pencil color on paper, 30×22

What can people do when they go to an exhibit, or are standing in front of a piece at a museum? What can we do to be a better listener and have a more genuine, authentic experience with art?

K: If you know you’re going to a museum to see a specific exhibition, it wouldn’t take too much time to use technology to Google and look up that artist, group of artists, or theme of the exhibit – research a little bit. Then, when you go into the museum, they have wall text all over the place, just for that purpose. Spending some time with that will help you gain insight. If you are standing in front of a piece that you don’t quite connect with, the text will help you make the connection. Invest in this way, as opposed to quickly walking through a museum and clicking images with your phone.

We just have to learn how to listen and be present. Words like “consciousness” and “awareness” can be cliché and ubiquitous terms. But I think that we can’t over-emphasize those qualities and the value they hold. A common theme entrenched in all of my work is value. My work runs the spectrum from minimalism to being so damn busy and complicated. To me, the most interesting ones don’t give themselves away immediately. You have to spend a little time with them, and listen.

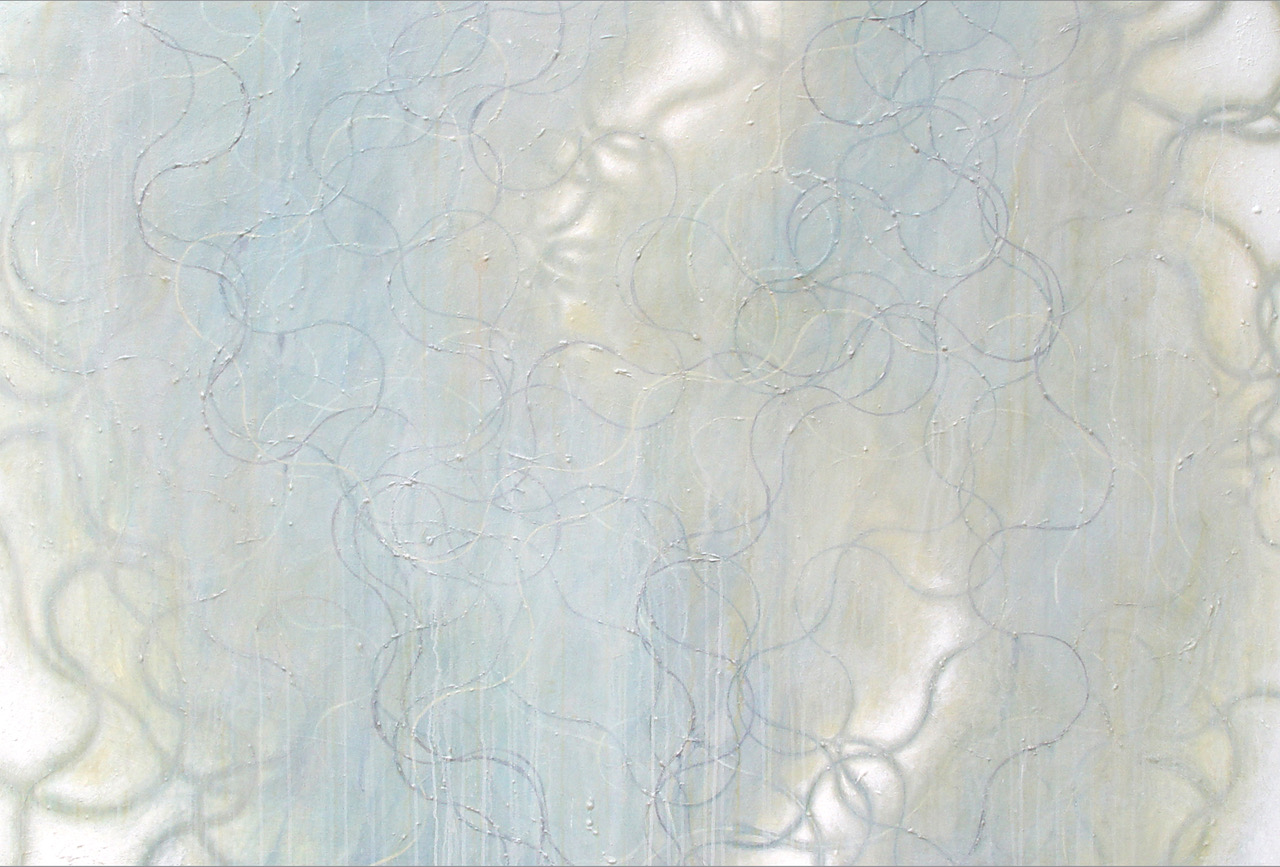

veil of whispers

2014, acrylic on canvas, 48×72

“the deepest soundings”

solo exhibition of Braille based work investigating language as value at ‘Fringe: an art experience,’ Ruston, LA

Oct. 1-29 Reception October 1, 4-6 pm